Making your games as diverse, accessible and inclusive as possible is not only the moral thing to do, it also opens your game up to a larger audience. How will people with a different sexuality react to your game? Different culture? Different age? Different gender?

Being diverse and inclusive is about acknowledging the differences we all have – and making sure that you think about how your game will affect everyone.

The advice in this article is only the start. As time goes on, the industry will learn more about how to be more inclusive – more advice will enter the conversation. But it takes effort to stay on top of these changes, so make sure you’re being proactive and regularly searching for new information to stay in the loop.

But for now, look at a few ways you can make more inclusive and diverse games.

Follow universal design principles

Before developing and designing your game, look into universal design principles. Using them as a basis, you should follow these seven principles:

- Make it equitable. So make sure that your game works for all people, and that if it can’t be identical for different people, it’s at least equivalent.

- Make it flexible. Give people the choice to change things that don’t work for them – whether that’s controls or the pace of the game.

- Make it simple. Make sure that your game’s user interface is easy to use, without a lengthy tutorial. And that the options are easy to find.

- Make it available. Give everyone a way to access the instructions, regardless of their physical or mental abilities. For example, how would a blind person read your tutorial?

- Make it safe. Think about how your game might affect people’s mental and physical health. Remove anything that could cause harm. And – if you can’t – at least give warnings.

- Make it effortless. Design your game so that people don’t need to strain themselves or do repetitive actions. And – if you can’t – make it easy to adjust the settings.

- Make it reachable. Make sure that anybody can see and reach the elements of your game, regardless of their body’s size or mobility.

Games for Change has a good process to make sure people are being inclusive, which you can apply to your studio. Adapting their seven steps, you should:

- Define. Figure out the potential problems and write down any barriers.

- Research. Look into those problems and get to know them inside out.

- Brainstorm. Get together and come up with possible solutions.

- Develop. Pick the best ideas and create prototypes of those.

- Review. Test the prototypes with a diverse group of testers and get feedback.

- Finalize. Add those prototypes into your actual game.

- Evaluate. Test and get feedback on your game to make sure you added those ideas in correctly. (And that nothing else in the game design interferes with your solutions.)

With this process you should be able to create a toolkit that addresses issues for all your games, not just the one you’re currently working on.

Give people options

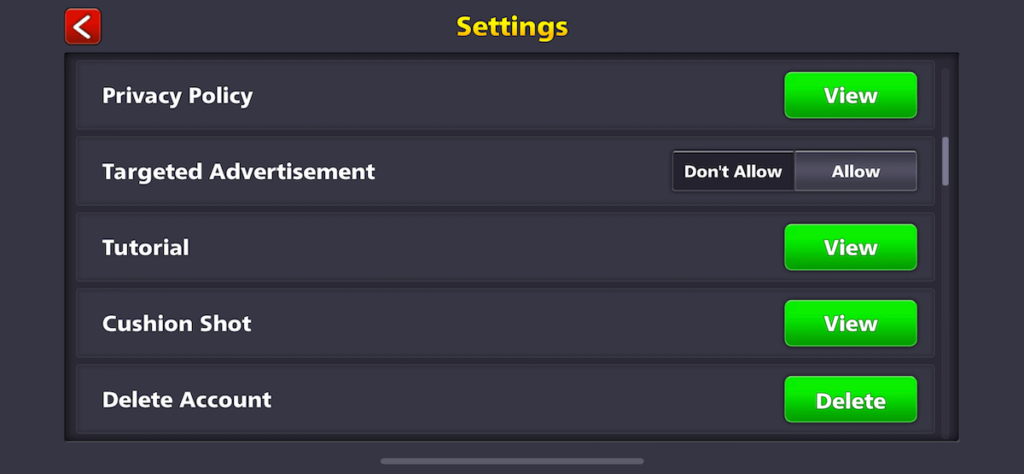

We’ve written before about how to make your game more accessible. And it almost always comes down to giving people options. Here’s what should definitely be in your settings menu:

- Subtitles. This helps people who are hard of hearing, as well as international players.

- Motion blur, head bobbing, depth of field. Some people can feel motion sick when playing games. These options help them find the right balance for themselves.

- Color palette. At the very least, add options for default, red-green friendly, and blue-yellow friendly. Or let people choose exactly what colors they want to use.

- Difficulty. Letting people choose an easier difficulty can be the difference between them being able to actually play your game or not.

- Controls. If someone only has one hand and you don’t have a way to remap the controls, they’re never going to be able to play your game.

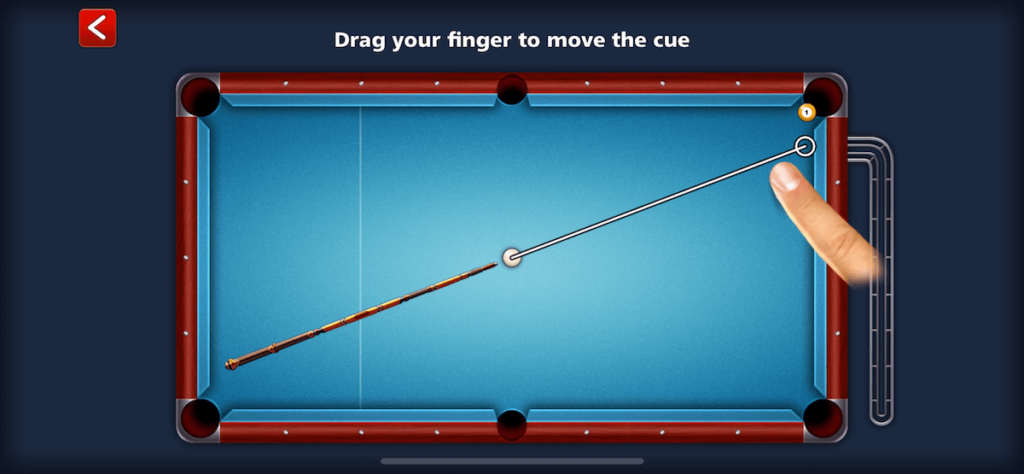

- Tutorials and hints. Let people turn back on tutorials, as they might not be able to remember everything.

- User interface elements. Let people turn off and on aspects of the user interface – or even move them around.

This is by no means an exhaustive list. But it’s definitely the bare minimum you should be doing to make your game accessible.

Just remember, it’s much easier to incorporate these aspects into your game if you start building the game from the ground up with them in mind.

Hire fairly and diversity will come naturally

One way to make more inclusive games is to have a more diverse team. The more varied your team, the more perspectives you’ll have in your team. And the best way to get to that point? Be fair in your hiring process.

If you focus on making your application process fair and equal – you’ll naturally hire a more varied and diverse team. It’s not about hitting a quota – it’s about giving everyone a fair chance.

Widen where you place job ads

If you only advertise your jobs on Mars, you’d only get martians applying. The same is true – if more complicated – if you advertise at specific universities or with specific newspapers.

Wherever you advertise, you’ll only get their audience’s demographic applying. So if you want to increase the pool of candidates, open up where you advertise your jobs. Widen the adverts, widen the pool.

Remove personal details from résumés

The more equal your process, the more likely you’ll hire a diverse team. If you hire purely based on achievements and experience, you’ll naturally overcome any possible biases. (As long as your adverts are in the right place.)

So ask your HR manager to replace the names, age, gender, race and photos on people’s résumés with placeholders. This is called ‘blind recruitment’. And it means that you’ll invite people to interviews based on their experience alone.

Some recruitment software can do this automatically. But you can get someone to do it manually (as long as they’re not involved in actually picking candidates).

Make an interview scorecard

The more you can get rid of subjective reasons when choosing who to hire, the more you’ll hire people fairly. So put together a checklist, assign each bullet point a score, and add them up at the end. Now, you can fairly compare candidates – without your personal biases possibly getting in the way.

For example, say a candidate reveals they have ADHD in the interview. Your gut reaction might be that they’ll be easily distracted and unable to perform the role. But if you use a scorecard – asking them specific questions about what they’ve done in the past – you’ll be able to judge their actual performance and skills. Rather than basing your decision on your assumptions about their life.

Find diverse playtesters, if nothing else

If you do all this and still find that your studio isn’t as diverse as you’d like, you can always make sure you’re getting lots of perspectives through your playtesters. For example, in VR – it’s important to get people of lots of different heights testing your game. If everyone who tests the game is tall, you can easily cause problems for shorter people.

If you search for playtesters from different countries and cultures, you’ll – at the very least – be able to catch potential problems before you release your game into the wild.

A diverse team is only the start

You also need to make sure that you’re treating your employees fairly and listening to all their views. But it’s a great start to making sure that you build a more diverse culture. Diverse cultures lead to diverse perspectives. And diverse perspectives lead to inclusive games.

Think about your characters

At this point, you should have a diverse team, a toolkit of solutions, and a standard set of options. You should be able to create an inclusive and accessible game.

Now it’s time to think about the creative side of your game. Your characters. Are they diverse? Is the story you’re telling inclusive? Have you fallen into the trap of making stereotypes, rather than rounded people?

Making a diverse game with a cast of characters from different backgrounds isn’t about hitting a quota. It’s about making sure that you’re not just falling into the habit of making characters that look and think just like yourself.

Don’t assign numbers to physical traits

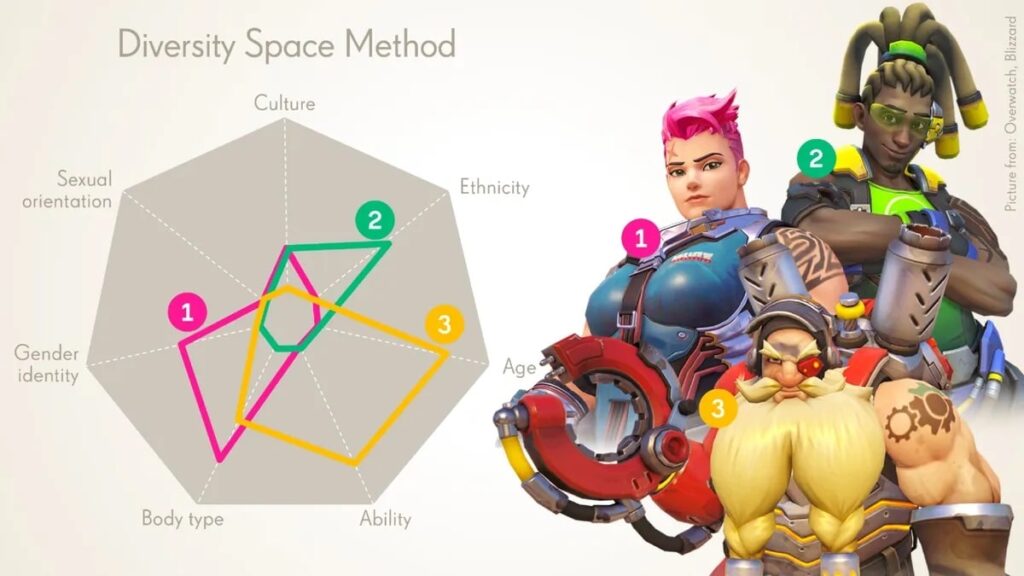

Activision infamously made an internal tool that – while it was meant to help them create diverse characters – inadvertently came across as clinical and creepy by players.

An example of how Activision’s tool ranks characters in Overwatch.

Why did this cause a problem? Because you can’t assign a number to these aspects. Why does Lucio, for example, rank so high on ethnicity? What makes him ‘more ethnic’ than other characters?

Assigning a number to traits like this is problematic. It puts a value on being one thing over another. That’s not the correct approach. It comes across as just ticking boxes: “Yes, we’ve got a gay.”

That doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t audit your cast of characters. You should go through your game and ask yourself: What sexuality, race, gender, and physical traits do our characters have? Doing that can help you combat your implicit biases – you might find that all your characters share pretty similar traits, because that’s what’s natural to you. Maybe they all come from the same background. Maybe they’re all the same age. If they are, an audit could help you spot those biases and help you change some of your characters.

Make rounded characters, not tokens

Ultimately, you want to make your characters believable. What you don’t want is to insert a character just to pay lip service to diversity. For example, adding a gay black friend or a damsel in distress. This is called tokenism – defining a character just by their physical traits. And adding them just because.

So don’t try and hit a quota. Instead, create round characters first. Ask yourself: Does their gender, race, or sexuality actually influence their motivations, desires and actions?

When creating a character, you want to start with their overall personality first. So note down:

- Their role in the story. Are they a hero or villain? Mentor or obstacle?

- Their virtues. What’s good about them? Are they just? Restrained? Patient? Courageous? Friendly? Kind?

- Their flaws. What’s bad about them? Are they lustful? An alcoholic? A gambler? Envious? Quick to anger? (Bear in mind, a disability isn’t a flaw. This is about their personality. Not what they can and cannot do.)

- Their motivations. What drives them? Why are they helping or hindering the hero? (Or, if they’re the hero, why are they on their quest?)

Now that you have their personality sorted, you can approach the rest of their character more fairly. Now is when you can come up with:

- Their backstory. How did they get to this point? Where were they born? What events in their life were important to them?

- Their traits. What’s their gender, race, sexuality and body type?

You can now go back over their personality and use their backstory and traits to influence their motivations, but never their virtues and flaws.

For example, a woman from an Indian background will have a very different upbringing to a man from Brazil. This might affect their motivations. But it wouldn’t mean that they’re no longer kind. Likewise, if the point of the character is that they’re rash – that also shouldn’t change, just because of their culture.

In other stories, maybe these traits affect how other characters treat this person. Does that influence their motivations? Are they fed up with being ignored or ostracised?

Question your internal biases

Making your game inclusive and diverse is really all about making sure you challenge your own biases. So be proactive and challenge yourself. Question whether your design or narrative is reaching as many people as possible.

And a key part of that is writing a story that’s true to the characters – not stereotypes or cliches. So if you’d like to learn more about how to craft that story, read our blog on how to improve your narrative.