When the motion picture became popular, the early filmmakers pioneered into a new medium and learned many valuable lessons. Their core takeaway can be summed up in three words: “Show, don’t tell.” It is almost always better to let the viewer see than it is to simply tell them what happened, because it makes the things the audience has seen more real to them. Games have undergone a similar sense of discovery and pioneering since the days of Pong, with a similarly evolved mantra. Perhaps the most important thing you can learn about designing games is the natural evolution of “show, don’t tell” - “Do, don’t show.”

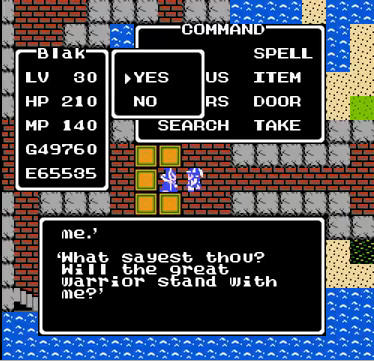

The main difference between a game and passive entertainment is that games require agency from the player in order to advance. The player has to actively do something to progress. The best games never forget this. In many games, even when you’re given no choice, you’re still given the illusion of a choice - you can try to refuse, even if your choice ultimately just puts you into an endless cycle. The simple fact that you make the player do something - push a button, move a character, place a piece, select a dialogue option, etc. pulls them in as an active participant even if the choice doesn’t make a difference. The action establishes a mental connection with the player, even if it is an unwilling one. It makes the player complicit with what is happening on screen because she has been advancing it, not because it is simply just happening outside of the player’s control.

This can be an incredibly powerful storytelling tool, because nothing puts the player into feeling like the protagonist more than actively doing the things that the protagonist needs to in order to advance the story. I’ve embedded perhaps the best example I’ve seen in recent memory below. Imagine this - Kratos is in the Elysium Fields, where his wife and daughter have gone for a blissful, happy afterlife. He would like nothing better than to stay there with them and be happy for the rest of eternity. But Persephone has declared her intent to destroy the world, Elysium included, and Kratos knows that if she succeeds, his wife and daughter would also be destroyed. So he must make that choice to defeat her. And then this happens (timestamp 5m52s):

At this point, the player must actively push away Kratos’ crying daughter in order to do what he must to save her by pressing the button. This is one of those situations where simply putting it into a cutscene would easily cause a separation of the player from Kratos - it’s a reminder to the player that Kratos is someone who would have to do such a horrible thing, which serves as a bit of a shock. But in this case, by forcing the player to actively participate in the scene, it actually reinforces to the player that sense of what it must feel like to be Kratos. You’re taking an active role in this, you’re making things happen, and you’re choosing to advance by making this little girl cry. She’s crying because of you. You can choose to make her stop. You can choose to make her cry even more.

Another incredible example is Call of Duty: Modern Warfare’s nuclear explosion scene. If you’ve played it, you’ll know what I’m talking about. During this scene, the player plays as an American soldier in an unnamed middle eastern nation. The most important thing here is that, while the game designers restricted the player from his or her full range of gameplay abilities, it still allows the player to look, shoot, and throw grenades - all core elements of being a soldier. Then once the explosion goes off, the player still retains control to an extent - he can still crawl where he likes. But the end is still inevitable - the soldier is doomed. By giving the player an active role in his avatar’s own death, it helps reinforce that the protagonist was real. It is far more immersive and engaging than passively watching it happen.

When you’re sitting down to write and design your story, you must remember this. Keep asking yourself what the player is doing at any given point. Make a list of verbs to describe what the player is doing - fighting, catching fish, pushing away his daughter, exploring, climbing, flying, sailing, etc. Try to keep these verbs as active as possible, and try to refrain from taking control away from the player as much as you can. Try to minimize giving the player extended periods of time where they cannot actively play. Everything should serve the greater purpose of advancing the play experience, the engagement, and the immersion. It’s actually even more important than the plot! Build your content in a way that facilitates player activity, not passivity. Do, don’t show.